Any collection of people that is faced with accomplishing some complex task faces two issues: how to divide up the labor, and how to coordinate their efforts. How this is done is the heart of what we mean by organizational structure.

There are two aspects of this issue. First, there are technical aspects of the task which determine in what way and to what extent you can break up the task into subtasks that can be performed by a single person. This often determines what jobs or positions may exist in the organization. There is some discretion here, but in general there is not a lot that an organization can do to change how this is done short of adopting a different technology altogether.

Second, there is the allocation of people to jobs. People have different competencies, and are better placed in certain jobs rather than others. They also have different interests, and so have different levels of motivation for different jobs. Placing people in the right jobs is a crucial strategic issue. Misusing talent, such as promoting the best engineer in the company to a pure management job that he or she has no interest or competence in, is a waste at best and dangerous at worst.

As organizations enter the 21st century, the source of competitive advantage is increasingly human resources. This may sound strange in a technological age where machines do more and more of the work, but it is precisely technology that creates this dependence on human resources. This is because technology is knowledge-driven. It is all about understanding how things work and being able to exploit that knowledge to solve client problems. The most important resource most organizations have is human smarts (exceptions are oil companies and other natural resource exploiters).

Given that the key problem in division of labor is the assignment of people with certain competencies and interests to tasks, part and parcel of the division of labor is the notion of specialization. Suppose you are xeroxing a set of student papers. Let's say there are 21 people in the class and each one has written a 5-page paper which has been stapled together. Now you want to make a copy of every paper to give to every other student and the professor so that everyone can critique everyone's paper (what a nightmare!). That's 21 copies of 21 5-page papers that have to xeroxed and then stapled together (because the stapler built into the copy machine never works).

Suppose you have two assistants (so there's three of you doing this). There are two obvious ways to divide up the labor. One is to give each person seven of the papers and then have them each do three steps on their seven papers: 1) unstaple the originals; 2) make 21 copies; 3) staple each of the copies. Assume that you have only one Xerox machine. So everyone starts unstapling their originals. Then, one person gets to use the Xerox while the others wait. When she's through, she starts stapling the copies while another person starts Xeroxing. This could take quite awhile.

The other way to divide up the labor is to have everyone unstaple, then one person starts xeroxing, another person starts stapling a moment later, and the third person ferries new copies from the Xerox to the stapler. This could be done much faster than the other way. This is the method of specialization into jobs or roles.

(At this point, you might want to look at the handout on departmentation. You'll see that these two ways of dividing the labor correspond to departmentation by product/market (the first one) and by function (the second one).)

Note that one of the reasons why the second method works better is that there was only one Xerox machine. What if there had been three Xerox machines? Well, then there wouldn't be so much difference between the two methods of dividing up the labor, though it is probable that the second method would still be a bit faster. One reason is that by restricting each person's job to just one task which is performed repetitively, you eliminate switching time (finding the unstapler, then moving the stuff over to the Xerox, then moving it all back, etc.). Another reason is that when people do one thing over and over again, they get really good at it. They have a chance to develop job competency. In combination with pairing up people who have certain talents with the jobs that need those talents, this can really result in productivity gains.

Notice that I haven't even mentioned the really slow way to do this task: each person takes each copy all the way through the process. In other words, she starts with the first original, unstaples it, then makes one Xeroxed copy, then staples that. Then she makes another copy, then staples that, and so on twenty-one times. Then starts with the second original. Nobody would do it this way because we automatically group similar tasks together to be done consecutively.

There are three basic coordinating mechanisms: mutual adjustment, direct supervision, and standardization (of which there are three types: of work processes, of work outputs, and of worker skills).

This mechanism is based on the simple process of informal communication. It is used in very small companies, such as a 5-person software shop, or for very, very complicated tasks, such as putting the first person on the moon. Mutual adjustment is the same mechanism used by furniture movers to maneuver through a house, or paddlers to take a canoe downriver, or jazz musicians playing a live engagement. It's especially useful when nobody really knows ahead of time how to do what they're doing.

Achieves coordination by having one person take responsibility for the work of others, issuing instructions and monitoring their actions. An example is the offensive unit of a football team. Here, there is marked division of labor and specialization, and the efforts of the players are coordinating by a quarterback calling specific plays.

If the organization is large enough, one person cannot handle all the members, so multiple leaders or managers must be used, then the efforts of these people (the managers) are coordinated by a manager of managers, and so on.

A third mechanism of coordination is standardization. Here, the coordination is achieved "on the drawing board", so to speak, or "at compile-time" if you like, not during the action or "run-time". The coordination is pre-programmed in one of three ways:

Work Processes. An example is the set of assembly instructions that come with a child's toy. Here, the manufacturer standardizes the work process of the parent. Often, the machinery in a factory effectively standardizes work by automatically providing only, say, blue paint when blue paint is needed, and only red paint when red paint is needed.

Outputs. Standardized outputs means that there are specifications that the product or work output must meet, but aside from that the worker is free to do as they wish. Stereo equipment manufacturers have a lot of freedom in designing their products, but the interface portions of the product (the connections to other stereo devices like CD's, speakers, tape-recorders, etc.) must be the same as everyone else's, or else it would be hard to put together a complete system.

Worker Skills. Professional schools, like medical schools, law school, business school, produce workers that do stuff exactly the same way. How do you treat a staphyloccocus infection? You use one of the following antibiotics. It's a series of recipes that are memorized. Employers (e.g., hospitals) can rely on these employees (physicians) to do things the standard way, which allows other employees (e.g., nurses) to coordinate smoothly with them. When a surgeon and an anesthesiologist meet for the first time in the operating room, they have no problem working together because by virtue of their training they know exactly what to expect from each other.

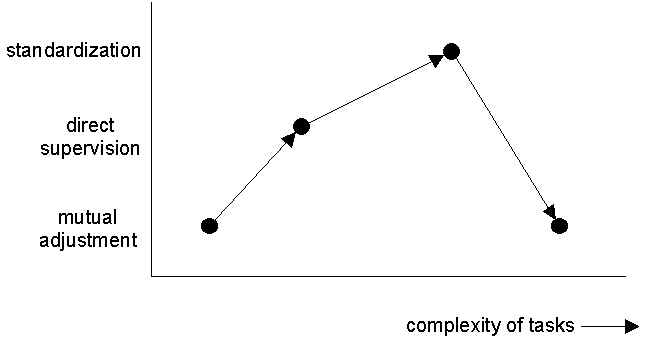

Simple tasks are easily coordinated by mutual adjustment. As organizational work becomes more complicated, direct supervision tends to be added and takes over as the primary means of coordination. When things get even more complicated, standardization of work processes (or, to a lesser extent, of outputs, or of skills) takes over as primary, but in combination with the other two. Then when things become really complicated, mutual adjustment tends to become primary again, but in combination with the others.

| Copyright ©1996 Stephen P. Borgatti | Revised: April 02, 2002 | Go to Home page |